The software engineering classic The Pragmatic Progammer popularised the benefits of orthogonality in software design. They introduce the concept by describing a decidedly non-orthogonal system:

You’re on a helicopter tour of the Grand Canyon when the pilot, who made the obvious mistake of eating fish for lunch , suddenly groans and faints. Fortunately, he left you hovering 100 feet above the ground. You rationalize that the collective pitch lever [2] controls overall lift, so lowering it slightly will start a gentle descent to the ground. However, when you try it, you discover that life isn’t that simple. The helicopter’s nose drops , and you start to spiral down to the left. Suddenly you discover that you’re flying a system where every control input has secondary effects. Lower the left-hand lever and you need to add compensating backward movement to the right-hand stick and push the right pedal. But then each of these changes affects all of the other controls again. Suddenly you’re juggling an unbelievably complex system, where every change impacts all the other inputs. Your workload is phenomenal: your hands and feet are constantly moving, trying to balance all the interacting forces.

[2] Helicopters have four basic controls. The cyclic is the stick you hold in your right hand. Move it, and the helicopter moves in the corresponding direction. Your left hand holds the collective pitch lever. Pull up on this and you increase the pitch on all the blades, generating lift. At the end of the pitch lever is the throttle . Finally you have two foot pedals, which vary the amount of tail rotor thrust and so help turn the helicopter.

As the authors explain:

The basic idea of orthogonality is that things that are not related conceptually should not be related in the system. Parts of the architecture that really have nothing to do with the other, such as the database and the UI [user interface], should not need to be changed together. A change to one should not cause a change to the other.

This applies to many types of design, not just for computer systems. The plumber should not have to depend on the electrician to fix a broken pipe.

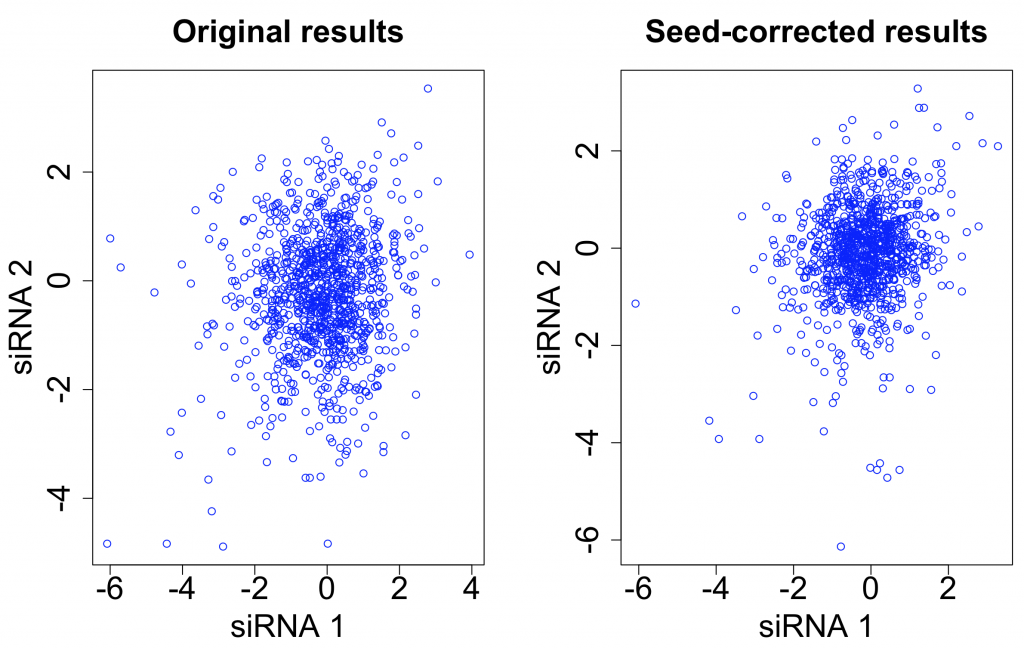

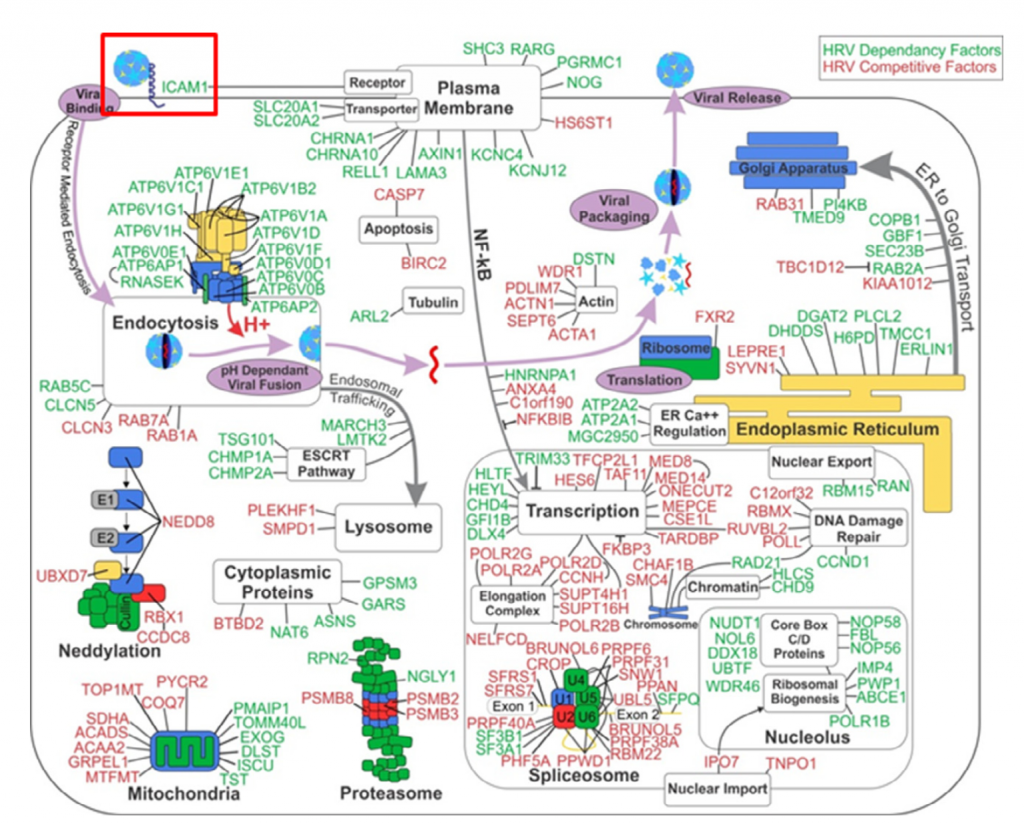

The principle has also been used in RNAi screening, notably by Perreira et al. who introduce the MORR (Multiple Orthologous RNAi Reagent) method to increase confidence in screening hits. Comparing the results of siRNAs from different manufacturers is important, but because they operate by the same mechanism (including the off-target effect), they are not really orthologous. More orthologous would be the comparison between RNAi and CRISPR experiments, which sometimes show discrepancies that point to interesting biology.

To confirm RNAi screening hits, ‘partial orthogonality’ may be preferable. If screening hits are due to either on-target or off-target effects, confirmation with RNAi reagents that only have one or the other would be better than using CRISPR, where it is difficult to interpret the reason for discrepancies (e.g. is there no phenotype because of genetic compensation?).

One could use C911s to create a version of the siRNA that, in theory, maintains off-target effects but eliminates on-target effects. We have observed, however, that C911s often give substantial knockdown of the original target gene (in some ways, C911s are like very good microRNAs). To be sure that a positive effect with C911s is not due to partial knockdown, one would also need to test that via qPCR. C911s can create a lot of work.

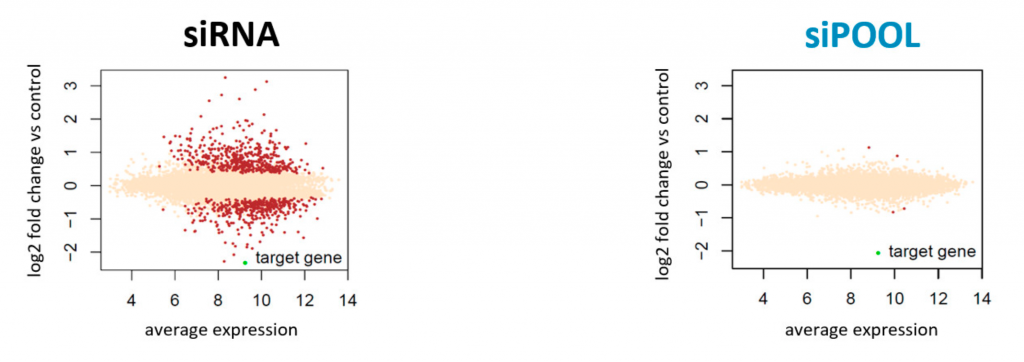

Far better would be to confirm screening results with siPOOLs, which provide robust knockdown and minimal off-target effects.

One place RNAi practitioners would hope not to find orthogonality is the relationship between on-target knockdown and phenotypic strength.

Since the early days of RNAi, positive correlation between knockdown and phenotypic strength has been suggested as a means to confirms screening results. Reagents with a better knockdown should give a stronger phenotype.

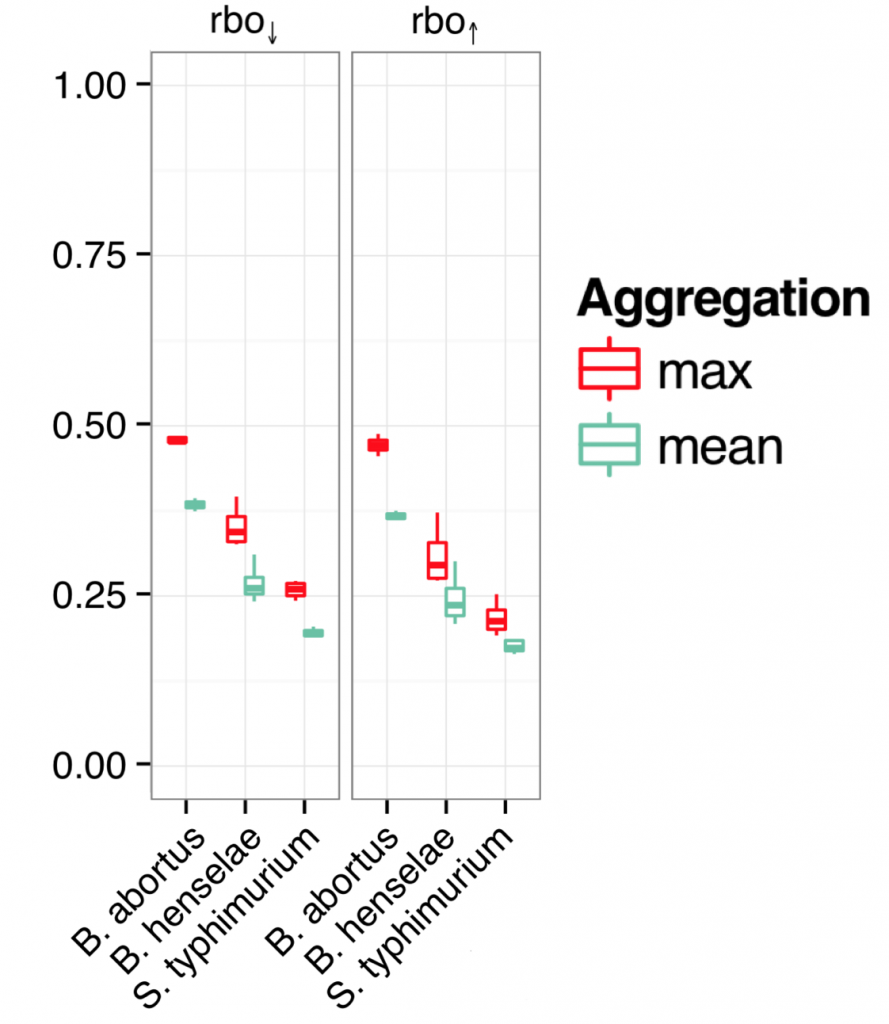

To test this, we obtained qPCR data for over 2000 siRNAs (Neumann et al.) and checked the performance of those siRNAs against the designated hit genes from an endocytosis screen (Collinet et al.).

If the siRNAs work as expected, those siRNAs with better knockdown should give stronger phenotypes than those with weaker knockdown.

There were 100 genes from the Collinet hits for which there were 3 siRNAs with qPCR data.

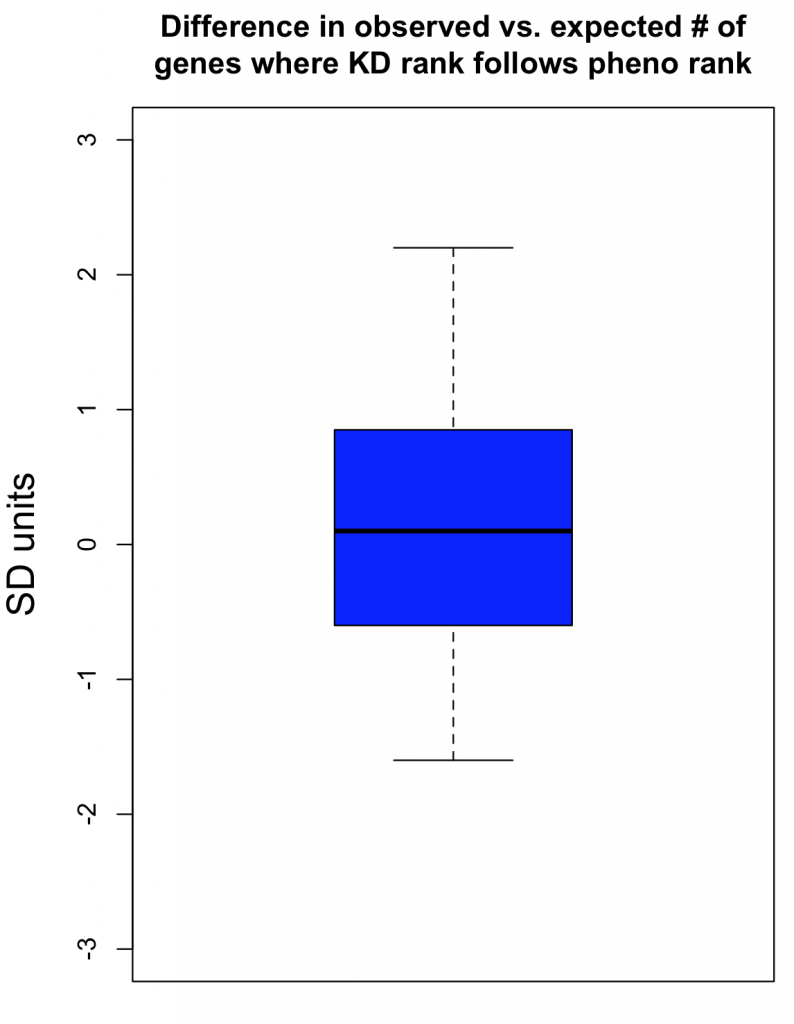

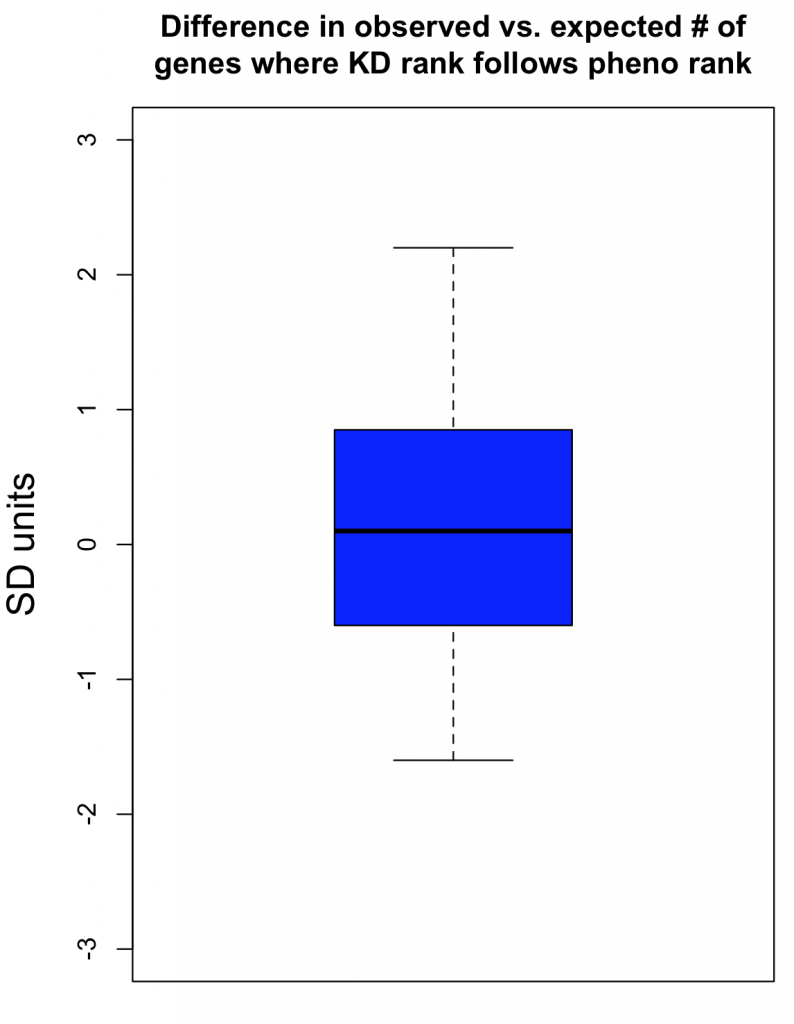

For those 100 siRNAs triplets, we compared the phenotypic ranks with the knockdown ranks. (We were agnostic about the direction of phenotypic strength, and checked whether knockdown and phenotype were consistent when phenotype scores were ranked in either ascending or descending order). For example, if siRNAs A, B, and C have phenotypic scores of 100, 90, 70 and knockdown of 15%, 20%, 30% remaining mRNA, we would say that phenotypic strength is consistent with knockdown (and because we were agnostic about phenotypic direction, we would also say it was consistent if siRNAs A, B, and C had scores of 70, 90, 100).

The observed number of cases where knockdown rank was consistent with phenotypic rank was then compared to an empirical null distribution, obtained by first randomising the knockdown data for the siRNA triplets before comparison to phenotypic strength. This randomisation was performed 300 times. This provides an estimate of what level of agreement between knockdown and phenotype would be expected by chance. The standard deviation (SD) from this null distribution was then used to convert the difference between observed and expected counts into SD units.

The Collinet dataset provides data for 40 different features. The above procedure was carried out for each of the 40 features.

To take one feature (Number vesicles EGF) as an example, we observed 34 cases where knockdown was consistent with phenotypic strength. By chance, we would expect 33.4 (with a standard deviation of 4.9). The difference in SD units is (34-33.4)/4.9 = 0.1.

As can be seen in the following box plot, the number of SD units between observed and expected counts of knockdown/phenotype agreement for the 40 features is centered near zero (median is 0.1 SD units):

This suggests that there is very little, if any, enrichment in cases where siRNA knockdown strength is correlated with phenotypic strength. The orthogonality between knockdown and phenotype, given the poor correlation between siRNAs with the same on-target gene, is unfortunately not unexpected.